A digital art and interviews project by Nathan D. Horowitz and Nicola Winborn

Nathan D. Horowitz speaks to Marsh Flower Press

Marsh Flower Press: What digital tools, Apps, processes etc. do you use in your art practice? Which ones have you used in ‘26 Visions – A Collaboration’?

Nathan: I use Midjourney AI. I hesitate to term AI image-making an art practice. My argument for why it isn’t art is that it’s extremely easy to do. My argument for why it is is that when I get into the flow, I like it a lot. My conclusion is that it both is and isn’t.

My term for it is art*. With the asterisk, I acknowledge objections and concerns: AI imagery rips off real artists, and AI itself is terrifying. With the asterisk, I say, “F*ck yeah, I completely understand and agree.”

The is-and-isn’t-ness applies, further, to the fundamental question of AI, that being: Is it intelligence or not? In one sense, yes, it is; in another, no, it isn’t.

Marsh Flower Press: What first drew you to the original analogue art work your sets of digital images are based on?

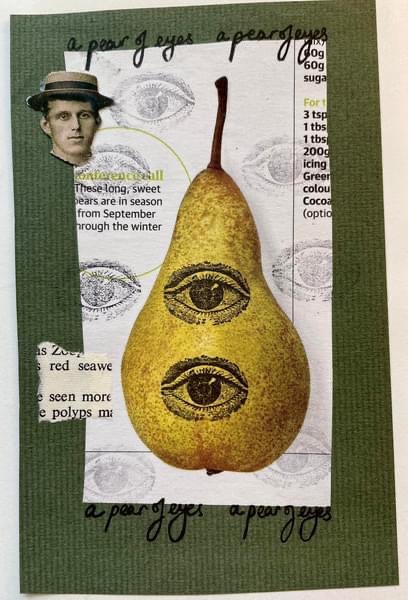

Nathan: The phrase “A pear of eyes” is written on the analogue collage four times. Nicola used a stamp to print two eyes – aligned vertically, rather than horizontally – on a color image of a pear. I liked the pun. Also, Nicola seemed to have given personhood to the fruit.

Maybe each thing has a soul. Maybe the eyes made it easier to see (and I mean that in both senses). Stamping the eyes on the pear greatly transformed it, and that’s part of the magic of visual art – making something new.

The eye stamp seemed to have been adapted from an engraving; the eyes seemed 19th or early 20th century, as did a photo of a man. The pear was an illustration on a page of recipes; by not cutting out the pear, Nicola let some of the text into the image: “3tsp / 1tbs / 1 tbs / 200g / icing / Green / colou / cocoa”. Nicola also added another bit of cut-up poetry from a different source on natural history: “s Z /red seawe / seen more / polyps”.

The imagery enchanted me and I thought it would likely remix nicely in AI. I experienced some conniptions about doing this and so I wanted to be transparent with Nicola and let her veto the results.

Marsh Flower Press: How do you respond to the digital images you’ve created here?

Nathan: It’s extremely fun to have chance encounters with images like these, which feel so much like the ones we see in dreams and visions. Often these images seem like photos of real events in the multiverse. Or illustrations of unwritten poems.

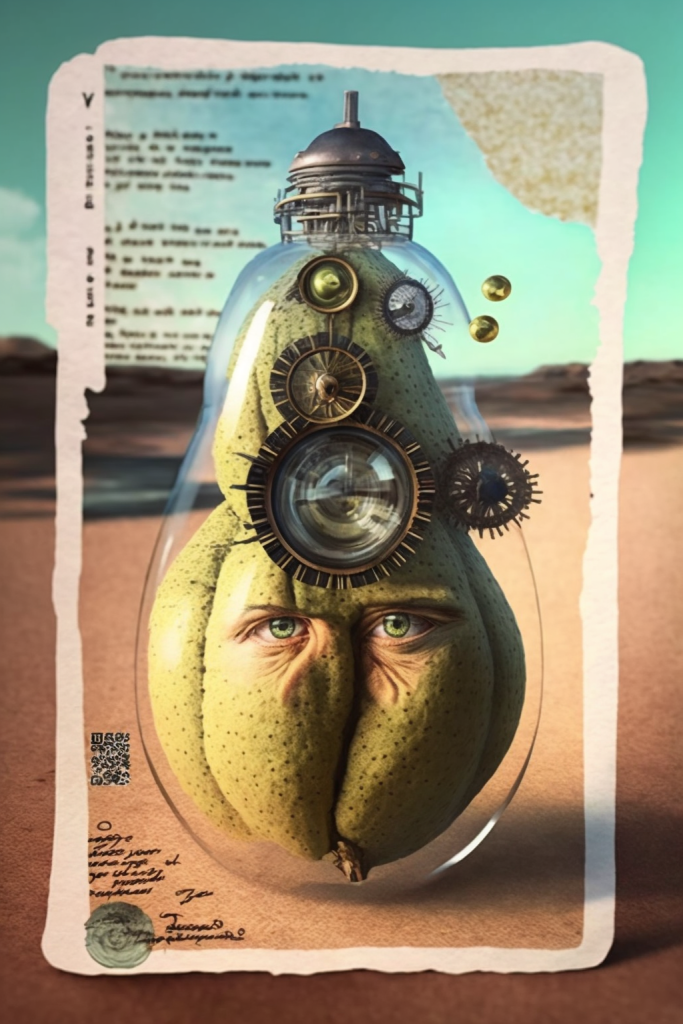

One of the resulting AI images that impressed me most when I first saw it, shows a kind of military surveillance pear drone. I mixed Nicola’s image with someone’s prompt that conjured an armored military vehicle. The result is magical. The image is vertically oriented and looks a bit like a card or a poster. There’s a rough white frame within the image that frames the drone itself. The frame is stamped and written on, in the style of a military report; that’s how the AI interpreted the text in Nicola’s original image. The scene is a sand dune in a desert with a few scrubby grasses. The drone is a pear with two human eyes, pale blue and reliable, oriented horizontally, looking at the viewer. The pear is within a clear shell of a material that looks like glass or plastic but is probably much stronger, as well as weightless. The shell has a built-in, huge, versatile camera as well as several other sensing apparatuses. I liked the pear drone because it made connections I would not have made by myself, at least not consciously. In that sense, AI art* is like long-lasting images from lucid dreams. Like a figure in a dream, the pear drone seems to be communicating, if only with their eyes.

Some other images are horizontally oriented. These feature Nicola’s image paired with someone’s prompt about a comfortable room in a house. Because Nicola’s image is vertical, in the horizontal image, the pear floats like a memory within a vertical rectangle like the middle stripe in a flag, while being reflected to either side.

Some images are square. In these, the pear is no longer visible. That is because I mixed it with an image from Facebook of five ceramic dog statuettes from Assyria from 650 BCE, each with its name written on it.

Making these images is like playing dice with the universe. I think that’s related to why it seemed to me one day that tarot was a kind of AI. These are ways to send out an inquiry. They return with an answer in a series of images.

Typically, I Midjourney while I proofread. I rewrite a sentence in an economics paper, I submit a request via text to Midjourney, and I go on to the next sentence.

This part of the process is out of our hands. Waiting for the images to develop, I’m reminded of the way we used to agitate a photo with rubber-tipped wooden tongs as it developed in the third chemical bath in the darkroom under the red light. At first, the photo would still be blank, but over about a minute and a half, it would develop, the darkest parts appearing first and then the others filling in.

After a few minutes, I’m likely to hear a chime telling me my images have developed. They arrive four at a time, in low resolution, and are never quite how I imagined they would be. It’s like an oven where you throw in some ingredients and find something unexpected when you open the door. The only constant is that the hands are messed up and people often have three legs. I choose one or more to upscale, that is, to recreate in a more developed and detailed way. The choice is a matter of taste. What looks good to me, I upscale, and if it still looks good, I’ll share it with others.

This is an “art” in which we’re outsourcing much of the creativity and building ephemeral Sistine Chapels with Dungeons and Dragons dice.

An unsatisfying aspect of this is that, in the end, all that we’ve done is create a certain digital pattern, in binary, of ones and zeros, of electrical impulses. However, the physicality is limited to the visual. No wool or wood to touch. No paint to smell. Just another reason to stare at a screen. A leading cause of headaches.

But it’s pleasurable, too. And if it’s true that making new neural connections is good for us, then AI art* is just the thing.

Marsh Flower Press: Some observers and practitioners are not comfortable with digital art, particularly AI applications. How do you feel about this disquiet?

Nathan: I kind of agree with it, as I noted above, and yet I mostly find myself on the other side of the debate. My position is that AI, including image making, is really interesting new terrain to study. It’s as if we’ve discovered a new continent located at the interface of hyperspace and the mind.

Next week: Marsh Flower Press interviews Nicola Winborn